What Happened to the Great Ideas? by John Berlau

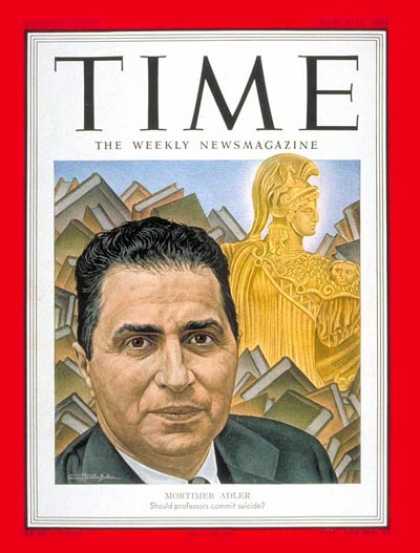

The following article has been reprinted with the kind permission of Insight Magazine and was originally published in August, 2001. The article briefly summarizes the life, work, and genius of Mortimer J. Adler, and discusses the profound influence he has made on education. Dr. Adler converted to Catholicism in the late years of his long life.

The following article has been reprinted with the kind permission of Insight Magazine and was originally published in August, 2001. The article briefly summarizes the life, work, and genius of Mortimer J. Adler, and discusses the profound influence he has made on education. Dr. Adler converted to Catholicism in the late years of his long life.

By John Berlau

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler recently passed away, but his legacy lives on in the Great Books programs he inspired and succeeded in establishing across the nation.

Mortimer J. Adler died in late June at the age of 98. Born in 1902, he was a philosopher and educator who lived through almost every year of the 20th century. But he was not a man of that century, at least not in establishment academic circles.

From the 1920s until his death, Adler most often was a voice in the wilderness crying out against educational trends he saw as destructive. He fought progressive education’s child-centered academic curriculum and vocation-centered training. Instead he championed general education in the classics. At a time when moral relativism has become dominant, Adler proclaimed that there still were universal moral truths to be found in the works of Plato and Aristotle.

Academics heaped scorn on him for writing about philosophy in simple terms for the masses in books with titles such as Ten Philosophical Mistakes and Six Great Ideas and Aristotle for Everybody: Difficult Thought Made Easy. He would maintain throughout his life that philosophy is everybody’s business.

Adler was dubbed the Lawrence Welk of the philosophy trade by one critic. Dwight MacDonald of the New Yorker derisively referred to Adler’s work as The Handy Key to Kulture. In the 1990s, when Adler and his colleagues released a revised edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica’s Great Books of the Western World, he was attacked viciously because the series contained few works by women and none from blacks. Harvard University’s Henry Louis Gates blasted the Great Books for showing profound disrespect for the intellectual capacities of people of color red, brown or yellow.

Adler calmly explained that the authors were chosen not because they were dead white males but because their work had stood the test of time. He noted that the guidebook for the series recommended many good books by blacks and women, as well as works by white male authors that didn’t make the cut. But a Great Book must be relevant to human problems in every century, not just germane to current 20th century problems, Adler wrote. The educational purpose of the Great Books is not to study Western civilization, Adler explained in the 1970s. Its aim is not to acquire knowledge of historical facts. It is rather to understand the great ideas.

Even in death, Adler still may be an outcast in academia, but he inspired legions of followers who have formed colleges, homeschooling cooperatives and Great Books discussion groups in major cities based on his ideas about education. And although his political positions often were of the left he once advocated socialism and world government some of his biggest champions today come from the political right.

The Great Books are alive and well as a powerful approach to education, Stephen Balch, president of the conservative National Association of Scholars, a group that pushes for a core curriculum of Western classics, tells Insight. It’s alive and well in large part because of his efforts as the architect of this kind of grand design for education. Those who favor an education in the service of civilization are in his debt for all the work he did over the years to establish the Great Books model and to bring the Great Books to the American population generally, not just those at colleges and universities. He certainly wanted as many people to read the Great Books as possible, based on a belief that they did speak to everybody.

The Great Books are alive and well as a powerful approach to education, Stephen Balch, president of the conservative National Association of Scholars, a group that pushes for a core curriculum of Western classics, tells Insight. It’s alive and well in large part because of his efforts as the architect of this kind of grand design for education. Those who favor an education in the service of civilization are in his debt for all the work he did over the years to establish the Great Books model and to bring the Great Books to the American population generally, not just those at colleges and universities. He certainly wanted as many people to read the Great Books as possible, based on a belief that they did speak to everybody.

Longtime conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly credits Adler with championing an education in Western classics to everyone, against the progressive educators who thought the classics were irrelevant to many students. Progressive educator John Dewey didn’t believe in individuals excelling in knowledge, Schlafly tells Insight. He believed that the purpose of education was to socialize people and have them do what they re told, and Adler was a good counterbalance to that.

In the early 1980s, Adler and his colleagues set forth a detailed program of primary schooling called Paideia , which is the Greek word for the upbringing of children. In his book The Paideia Proposal, Adler proposed that the education for all children must be general and liberal and nonspecialized and nonvocational, no matter the perceived intellectual capacity of the child. Using milk containers as an analogy, he said the half-pint container as well as the gallon container should be filled to the brim with the same quality of substance cream of the highest attainable quality for all, not skimmed milk for some and cream for others. Adler also emphasized that as much as possible the great works should be taught in the Socratic method, in which children discuss what they have read, rather than as a top-down lecture.

Today, the Paideia Group Inc. consults with schools wanting to set up programs. Adler, who was honorary chairman, sometimes would go in and lead the children of participating schools in discussions. I have such wonderful letters from students who have been in the seminars thanking Mortimer for what it has done for their lives, Paideia Group President Patricia Weiss tells Insight.

The Paideia Group concentrates on public schools, Weiss says, because Adler was such a strong advocate of universal public education. Still, she says, public schools often are resistant to change. She hopes that charter schools will give teachers and parents more flexibility to implement Paideia.

Meanwhile, the Great Books curriculum really is taking off in homeschooling. Patrick Carmack, who homeschools his children in Colorado, cofounded the Great Books Academy after reading Adler’s books on education in 1999. The program assigns Great Books for participating children to read and holds online Socratic discussion groups in the style that Adler proposed. The directors met with Adler in 2000, and his longtime colleague Max Weismann serves as chairman. Carmack says the curriculum is being used by parents in every state and internationally.

At the college level, St. John’s College offers a four-year nonelective Great Books program that Adler helped design in the 1930s. The college, which has campuses in Annapolis, Md., and Santa Fe, N.M., uses no textbooks, at Adler’s prompting. The only texts are the primary materials that students read and discuss. Textbooks merely are catalogs of information that essentially are undiscussable, Adler wrote.

At Wright College, a community college in Chicago, Bruce Gans started a Great Books elective course in which one-fifth of the student body now has enrolled. Gans faced objections from other faculty that works by dead white males wouldn’t go over well with their mostly black and Hispanic students going to school while working. But he tells Insight that every year he gets letters and notes on the final exams from such students saying how much reading the great works has bettered their lives.

Adler maintained that schooling did not make one educated; it merely prepared students for a life of learning. No one can be an educated person, while immature, Adler wrote in The Paideia Proposal. Only through the trials of adult life, only with the range and depth of experience that makes for maturity, can human beings become educated persons.

Adler himself knew the value of self-education. Hoping to be a journalist, he dropped out of school at 14 to become a copyboy at the New York Sun. After a year, he took night classes at Columbia University to improve his writing. Reading the autobiography of English philosopher John Stuart Mill for a class, he discovered that Mill had read Plato at age 5. He felt a sense of shame that he had not yet done so and borrowed Plato’s works from a neighbor. Adler was hooked, and he eventually got a scholarship to study philosophy at Columbia.

Adler’s experience in the working world led him to propose a mandatory two-year hiatus from all schooling after students graduated from high school, although this was not formally included in the Paideia plan. Only after experience in life and work would students really be eager to learn. Young people certainly cannot become mature as long as they remain in school; on the contrary, they suffer from prolonged adolescence, Adler wrote in his autobiography Philosopher At Large. That is a pathological condition which can be prevented only by getting the young out of school as soon after the onset of puberty as possible.

This way, Adler said, universities would be populated with students who return to educational institutions because they have a genuine desire for further formal study, instead of students who occupy space in our higher institutions as the result of social pressures. Regardless of whether a person went to college, Adler maintained that lifelong learning was essential for personal happiness. Adler defined happiness as Aristotle did, not as instant pleasures but the joy and satisfaction that comes from living a virtuous life. He never stopped learning and wrote more than 20 books after he turned 70. The loss of immediate or short-term memory that inevitably accompanies advancing years in no way diminishes the power of creative, analytic and reflective thought, Adler wrote in his second autobiography, A Second Look in the Rearview Mirror, published when he was 89.

Some say the example of Adler’s long life of learning may itself be one of his most enduring legacies. Half-jokingly, Balch says, Mortimer Adler is a great advertisement about the longevity you can attain reading Great Books. You have so many of these big challenging books to read that you ve got to live a long time to do them justice.

Reprinted with permission of Insight. Copyright 2001 News World Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.