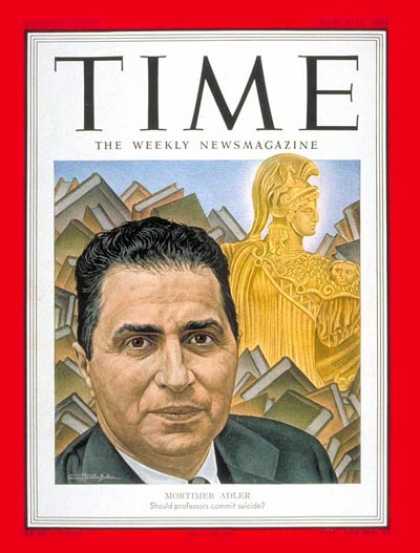

THE BLESSINGS OF GOOD FORTUNE by MORTIMER ADLER

THE BLESSINGS OF GOOD FORTUNE by MORTIMER ADLER

Early in life I learned a lesson from Aristotle. Whether or not we succeed in having lived a good life is not entirely a matter of free choice and moral virtue. Virtue is certainly a necessary condition; it may even be the most important factor; but by itself it is not sufficient. The other necessary, but also insufficient, condition is having good fortune. Fortune, good or bad, plays a part in everyone’s life. The accidents of fortune are the things that happen to you. When good luck happens, you may aid and abet it by seizing the opportunities it affords, but its happening to you is beyond your control. The only things entirely within your own power are the things you freely choose to do, and even some of these require attendant good fortune for them to be fully achieved.

You may take care of your health by virtuous conduct on your part, but your achievement of a healthy body may also require a healthy environment, which may or may not be your good fortune to enjoy. (In my youth, I went through serious influenza and poliomyelitis epidemics unharmed. Through diligent care by my parents I escaped being ill but, that was still a blessing of good fortune.) In a book in which I have recited the free choices I made to devote myself to teaching and learning, to writing books and editing them, and above all to the vocation of philosophy, it seems fitting that at its close I should briefly recount the incidents of good fortune with which I have been blessed. With the exception of one’s mate, one does not choose one’s family—parents, siblings, offspring, and in-laws. In these respects, I experienced good fortune, but not entirely. My parents came from good stock, as evidenced by their longevity and my own. I am grateful to them not only for the genes they bestowed on me, but also for their wise and benevolent treatment of me as a child, a schoolboy, and a college student.

My mother was a schoolteacher, disposed to encourage study on my part. My father’s German upbringing led him to demand excellence in that performance. Anything less than an A-A-A report card from school was severely frowned upon. In addition,I had the good luck of being their firstborn child, as my sister, Carolyn, will testify about the less-privileged status of being the second child. Though marriage falls within the range of free choice, it is also partly attended by unforeseeable consequences that are in the realm of chance. I was less fortunate in my first marriage than in my second. At my eightieth birthday party, I proposed, with regard t0 marriage, the maxim that if you don’t succeed at first, try again. I did, and it has worked wonderfully well.

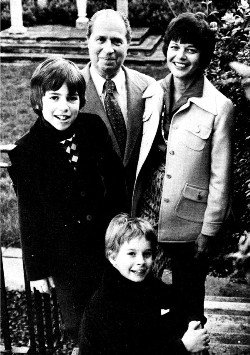

I think I summed this up at Caroline’s fiftieth birthday party, when I toasted her as “my best friend and severest critic.” It has been said that the smile on Adam’s face in the Garden of Eden betrays his enjoyment of the fact that he had no mother-in-law. In spite of the fact that Eleanor Pring, Caroline’s mother, was my mother-in-law, I still smile about my association with her and with Caroline’s two sisters, Polly and Margaret. The family I married into by choice has been, by good luck, as good for me as the family of my birth. Having two adopted sons in my first marriage with Helen was clearly a matter of choice. My second marriage with Caroline gave birth to two children, both boys, also matters of choice. But how Mark and Michael, the first two, and Douglas and Philip, the second two, have turned out has not been entirely within my control, or within Helen’s or Caroline’s.

I found the job of being a father taxing and difficult. I am quick to confess that I sometimes shirked my duties, did not devote enough of my time and energy to being a parent, and, in addition, was probably not temperamentally inclined to do better. Much that happened in the course of their upbringing may have been my fault, which I regret and for which I have tried to make amends, differently in each of the four cases. The four boys have matured at different rates of speed and under different circumstances, but the good fortune that I can now report is that they have finally developed into good human beings, enjoyable to be with, as well as good citizens.

Only the first two, Mark and Michael, are now married and have children—my grandchildren—to whom they are good parents. I hope I live long enough to see the other two, Douglas and Philip, married and with anticipated offspring. After one’s family, comes one’s friends. Here, too, I have been extremely fortunate. In a sense, of course, one chooses one’s friends, but acquaintance with the individuals with whom one later elects to develop a friendship is a happenstance.

Only the first two, Mark and Michael, are now married and have children—my grandchildren—to whom they are good parents. I hope I live long enough to see the other two, Douglas and Philip, married and with anticipated offspring. After one’s family, comes one’s friends. Here, too, I have been extremely fortunate. In a sense, of course, one chooses one’s friends, but acquaintance with the individuals with whom one later elects to develop a friendship is a happenstance.

Two individuals whom I became acquainted with accidentally because they happened to be students of mine in my early years of teaching at Columbia University, Clifton Fadiman and Jacques Barzun, have developed into lifelong friends, and have also become the friends of my wife, Caroline. I cannot recount all the ways in which friendship with them has influenced my life and my work; I am grateful that they have grown old along with me and are still alive.

The third friend of my early years, no longer alive, was Robert Hutchins, but as long as he lived, he and I were close friends. But my good fortune in meeting Bob in 1927 when he was acting Dean of the Yale School, was both so accidental and so consequential, that I must repeat here the story about it that I told in Philosopher at Large. (pp. 107-111) In 1925-1926, I wrote my first book, Dialectic, published in 1927. In it, while describing the process of argument and disputation, I dropped a footnote which said that this process is exemplified in the Anglo-American law of evidence. C. K. Ogden was editor of the series in which that book was published, and while visiting Hutchins at the Yale School early in 1927, Ogden was carrying the page proofs of one thirty-two-page unit from my book. It just happened to include the page in which I had placed that footnote about the Anglo-American law of evidence. While talking to Hutchins about other matters, Ogden mentioned me in a complimentary fashion and gave Hutchins the thirty-two-page unit of page proof he had been carrying in his pocket. So far, everything that happened was pure chance.

At that time, Hutchins was not only Acting Dean, but was also Professor of the Law of Evidence. The footnote caught his attention and, in June, he wrote me a letter, mentioning the footnote which he thought signified that I had a lively interest in the law of evidence. He invited me to come up to New Haven sometime that summer to discuss with him problems in the laws of evidence on which he was currently working. Now free choice came into play. Up to that point, I knew just enough about the law of evidence to make that footnote I had written substantially correct, but nothing more. I must have thought at the time that the invitation from Hutchin’s opened up an academic opportunity of which I should take advantage. So I wrote to Hutchins accepting his invitation and setting the time for my visit to New Haven in early August. I then spent the intervening time in July studying the law of evidence, by taking out of the law library J. H. Wigmore’s five-volume classic textbook on the subject. Since the brief opening pages of each chapter contained Wigmore’s explanation of the law on that subject, followed by pages of discussion of cases in the federal and the forty-eight state jurisdictions, I could read through Wigmore’s five volumes, skipping all the pages dealing with cases. As it turned out, when I met with Bob Hutchins in August, I appeared to him to have a firm grasp of the underlying principles of the law of evidence, and we hit it off in general. Shortly after my visit, I received a letter from him inviting me to leave Columbia and join him in New Haven to work with him on some essays he was planning to write about the psychological and philosophical aspects of certain rules of evidence, especially the hearsay rule.

I turned his invitation down, for no other reason, so far as I can remember, other than my unwillingness to change my residence from Manhattan Island, where I had been born and reared, to what, in comparison, was the sleepy little village of New Haven. My refusal to move to New Haven did not divert Hutchins from his aim to get me involved in work on the law of evidence. He came down to New York to persuade Young B. Smith, then Dean of the Columbia Law School, to have me work with Jerome Michael, his Professor of the Procedural Law of Pleading and Evidence. I did so, while still remaining an instructor in psychology. We co-authored a book, entitled The Nature of Judicial Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of the Law of Evidence, published in 1931.

I turned his invitation down, for no other reason, so far as I can remember, other than my unwillingness to change my residence from Manhattan Island, where I had been born and reared, to what, in comparison, was the sleepy little village of New Haven. My refusal to move to New Haven did not divert Hutchins from his aim to get me involved in work on the law of evidence. He came down to New York to persuade Young B. Smith, then Dean of the Columbia Law School, to have me work with Jerome Michael, his Professor of the Procedural Law of Pleading and Evidence. I did so, while still remaining an instructor in psychology. We co-authored a book, entitled The Nature of Judicial Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of the Law of Evidence, published in 1931.

Not only did that result in my friendship with Jerome Michael as long as he lived, and with whom I wrote another book, Crime, Law and Social Science, published in 1933, but it also led to a whole series of fortuitous consequences that represented a train of good fortune at work in the making of my life. First of all, when Hutchins in 1929 became, at the age of thirty, President of the University of Chicago, he invited me to join him there as an associate professor in three areas—in the philosophy and psychology departments and in the law school. My salary as a Columbia instructor, $2,400 a year, was to be increased to $6,000. Quite apart from that advantage, I had the good sense to perceive greater academic opportunities for me at Chicago than I would have had had if I had remained at Columbia. Since I was not yet disillusioned about the “Joys” of academic life, I went to Chicago, not only to teach in the philosophy and psychology departments and in the law school, but primarily to conduct a great books seminar for entering freshman in the college, with Bob Hutchins as my co-moderator. That was an opportunity I could not turn down, and my taking it has had many consequences, all fortunate for me. William Benton had been a classmate of Bob Hutchins at Yale.

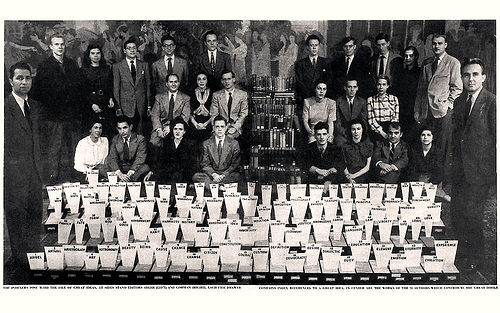

After he retired from the advertising firm of Benton and Bowles, Hutchins brought Benton to the University of Chicago, appointing him Vice-President in charge of Public Relations. Through my close association with Bob, I naturally came in contact with Bill Benton. This developed into a friendship that had many fortunate consequences for me, principally among which, after Benton became CEO of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., was my becoming Bob’s Associate Editor of the first edition of Great Books of the Western World, my producing the Syntopicon that went with that set, my eventually succeeding Bob Hutchins as Chairman of the Britannica’s Board of Editors, and my becoming Editor in Chief of the second edition of Great Books of the Western World. That is not all the good fortune that derived from my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He departed in 1951 from the University of Chicago to become Vice-President of the Ford Foundation. By that time I had become completely fed up with academic life, and, as a result of my creating the Syntopicon, I wished to spend my philosophical energies on producing the Summa Dialectica, a project I had conceived in 1927 when I wrote Dialectic.

After he retired from the advertising firm of Benton and Bowles, Hutchins brought Benton to the University of Chicago, appointing him Vice-President in charge of Public Relations. Through my close association with Bob, I naturally came in contact with Bill Benton. This developed into a friendship that had many fortunate consequences for me, principally among which, after Benton became CEO of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., was my becoming Bob’s Associate Editor of the first edition of Great Books of the Western World, my producing the Syntopicon that went with that set, my eventually succeeding Bob Hutchins as Chairman of the Britannica’s Board of Editors, and my becoming Editor in Chief of the second edition of Great Books of the Western World. That is not all the good fortune that derived from my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He departed in 1951 from the University of Chicago to become Vice-President of the Ford Foundation. By that time I had become completely fed up with academic life, and, as a result of my creating the Syntopicon, I wished to spend my philosophical energies on producing the Summa Dialectica, a project I had conceived in 1927 when I wrote Dialectic.

I could not do that as a Professor of Law, which I had then become at the University of Chicago. In 1952, through Bob’s good auspices, I received a large grant from the Fund for the Advancement of Education, established by the Ford Foundation to establish the Institute for Philosophical Research, of which I have been the President since 1952. The Institute produced the two volumes of The Idea of Freedom, after eight years of research and writing. It later produced dialectical treatments of the ideas of justice, happiness, love, progress, beauty, and religion and, after operating in San Francisco from 1952 to 1963, it was moved to Chicago by Bill Benton when he wanted me there to work editorially for Encyclopaedia Britannica, while at the same time directing the work of the Institute for Philosophical Research.

As I have said earlier in this book, if I had remained at the University of Chicago after Bob Hutchins left it, I could never have done the philosophical work that has been the joy of my last forty years. Bob’s enabling me to leave the University of Chicago and all the distractions and intrigues of academic life, and his enabling me to establish the Institute for Philosophical Research as the ivory tower in which the kind of philosophical work I wished to do could be accomplished, was certainly the greatest stroke of good fortune In my professional life. I am still not finished with Bob Hutchins as my guardian angel. It was through his friendship with Walter and Elizabeth Paepcke that I also became their friends, and it was through them (as I have related earlier) that I became involved in the Aspen Institute after Walter established it in 1950. Meyer Kestnbaum, CEO of Hart Schaffner and Marx, another friend of Hutchins and mine, brought the Institute for Philosophical Research to the attention of Arthur Houghton, Jr., at a conference held at the Corning Glass Works that Arthur attended.

I subsequently met Arthur at a conference in New York, which was sponsored by the Institute for Philosophical Research while it was working on the idea of freedom. That led to Arthur Houghton’s becoming a substantial contributor to the budget of the Institute after the Ford Foundation grant expired; and, more important than that, Caroline and I developed a close friendship with Arthur, with whom we traveled extensively abroad. There is still one further consequence of my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He introduced me to Henry Luce, the co-founder of Time magazine, and to his wife Clare, both of whom, as I have related, came to Aspen in August of 1950. We became friends and Caroline’s and my friendship with Clare continued many years after Henry’s death.

I subsequently met Arthur at a conference in New York, which was sponsored by the Institute for Philosophical Research while it was working on the idea of freedom. That led to Arthur Houghton’s becoming a substantial contributor to the budget of the Institute after the Ford Foundation grant expired; and, more important than that, Caroline and I developed a close friendship with Arthur, with whom we traveled extensively abroad. There is still one further consequence of my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He introduced me to Henry Luce, the co-founder of Time magazine, and to his wife Clare, both of whom, as I have related, came to Aspen in August of 1950. We became friends and Caroline’s and my friendship with Clare continued many years after Henry’s death.

I do not know this for a fact, but I think Clare had something to do with the cover story in Time about me and the Syntopicon, written by Henry Grunwald, who was then Senior Editor under Otto Fuerbringer as Managing Editor. In any case, I have enjoyed my friendship with Henry Grunwald in the subsequent years when he became Managing Editor of Time and then Editor-in-Chief of Time Inc.; and, after retiring from that position, became U.S. Ambassador to Austria. Caroline and I visited him and his wife Louise in Vienna and spent an enjoyable weekend at the Ambassador’s residence there.

Mentioning my involvement in the Aspen Institute as a fortuitous consequence of the great good fortune of my friendship with Bob Hutchins, I must also mention one other fortunate happenstance. Larry Aldrich, a famous dress designer, came to Aspen to participate in one of my seminars there early in the 1970s. Since then, Caroline and I have become close friends with Larry and his wife Wynn. We have traveled with them on many pleasant excursions here and abroad. Larry, having retired from the dress business, established the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, in Ridgefield, Connecticut. His knowledge and expertise in the field of the visual arts has enriched my life; Wynn’s knowledge of cuisines and gourmet skill in cooking, which my wife Caroline shared, sent them abroad together to cooking schools in Paris and Bologna.

I hope I have now made clear how one stroke of great good fortune—in this case, my friendship with Bob Hutchins—led to a train of consequences, all of them fortunate happenings. There are still others that I have not so far mentioned, friendships that have been fortunate for me, but not connected with Bob Hutchins. One was the influence on my life of my friend Arthur Rubin, a friendship that began in the library of the Psychology Department at Columbia when I was still an undergraduate student in the college. This continued until his death. He saw me through the ordeal of my divorce from Helen and later celebrated my marriage to Caroline. He was extremely helpful to me in the rearing of our children. One thing that I should not forget to mention was the inspiration I got from Arthur for the production of the Summa Dialectica at the time I talked to C. K. Ogden about the idea for my first book. That, by the way, was another lucky happenstance. I met Ogden at a tea party given by Gardner Murphy, an associate of mine in the Psychology Department. Ogden mentioned a book he was editing by Boris Bogslavsky, to be entitled The Art of Controversy. It was that title, I think, which prompted me to outline another approach to the clarification and resolution of philosophical conflicts. Whatever I said caught and held Ogden’s attention. He then and there invited me to submit a draft of the book I had outlined. That was in November. I wrote the book over the Christmas recess and during the January examination period, and delivered it to Ogden on the first of February.Another of my lifelong friendships began when I taught a course in the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago. Philip Rosenthal was a student in that class. After that chance encounter, we met again many years later when we were both guests of Mortimer and Janet Fleishhacker on a cruise of the Greek islands. He helped me through many difficulties in my last years in San Francisco, difficulties both personal and professional.

I hope I have now made clear how one stroke of great good fortune—in this case, my friendship with Bob Hutchins—led to a train of consequences, all of them fortunate happenings. There are still others that I have not so far mentioned, friendships that have been fortunate for me, but not connected with Bob Hutchins. One was the influence on my life of my friend Arthur Rubin, a friendship that began in the library of the Psychology Department at Columbia when I was still an undergraduate student in the college. This continued until his death. He saw me through the ordeal of my divorce from Helen and later celebrated my marriage to Caroline. He was extremely helpful to me in the rearing of our children. One thing that I should not forget to mention was the inspiration I got from Arthur for the production of the Summa Dialectica at the time I talked to C. K. Ogden about the idea for my first book. That, by the way, was another lucky happenstance. I met Ogden at a tea party given by Gardner Murphy, an associate of mine in the Psychology Department. Ogden mentioned a book he was editing by Boris Bogslavsky, to be entitled The Art of Controversy. It was that title, I think, which prompted me to outline another approach to the clarification and resolution of philosophical conflicts. Whatever I said caught and held Ogden’s attention. He then and there invited me to submit a draft of the book I had outlined. That was in November. I wrote the book over the Christmas recess and during the January examination period, and delivered it to Ogden on the first of February.Another of my lifelong friendships began when I taught a course in the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago. Philip Rosenthal was a student in that class. After that chance encounter, we met again many years later when we were both guests of Mortimer and Janet Fleishhacker on a cruise of the Greek islands. He helped me through many difficulties in my last years in San Francisco, difficulties both personal and professional.

Since then, Philip has spent many summer weeks with Caroline and me in Aspen where, auditing my seminars, he has renewed our relationship as student and teacher. A third has been the friendship that Caroline and I developed with Andrew and Shawn Block in Chicago, resulting from the fact that their children and ours were pupils in the elementary grades at Francis W. Parker School. Shawn and Caroline were thrown together by their interest in the affairs of the school. Out of that blossomed the warm friendship that has enriched our subsequent years in Chicago. Glancing over the pages of Pbilosopber at Large to jog my memory of blessings that have befallen me, I found one of great importance to my life as a whole, one so important that I should not overlook it here. It is the fact that, with very few exceptions, all the work I have done in my life has consisted of activities that I consider leisuring rather than tolling; in other words, ctivities that one would engage in if one did not need monetary compensation for doing so, as opposed to the kind of drudgery that no one would undertake without being compensated for it. Let me quote the paragraph from Philosopher at Large that eloquently describes this fortunate circumstance.

Since then, Philip has spent many summer weeks with Caroline and me in Aspen where, auditing my seminars, he has renewed our relationship as student and teacher. A third has been the friendship that Caroline and I developed with Andrew and Shawn Block in Chicago, resulting from the fact that their children and ours were pupils in the elementary grades at Francis W. Parker School. Shawn and Caroline were thrown together by their interest in the affairs of the school. Out of that blossomed the warm friendship that has enriched our subsequent years in Chicago. Glancing over the pages of Pbilosopber at Large to jog my memory of blessings that have befallen me, I found one of great importance to my life as a whole, one so important that I should not overlook it here. It is the fact that, with very few exceptions, all the work I have done in my life has consisted of activities that I consider leisuring rather than tolling; in other words, ctivities that one would engage in if one did not need monetary compensation for doing so, as opposed to the kind of drudgery that no one would undertake without being compensated for it. Let me quote the paragraph from Philosopher at Large that eloquently describes this fortunate circumstance.

Looking back on my life since I left home, I count myself unusually fortunate that, during more than fifty years of earning a living, almost all the work I have elected to do has consisted of tasks that I would gladly have taken on even if I had had an independent income. If leisure work, as opposed to drudgery, comprises all those activities in which one would engage for reasons of intrinsic reward and without need of extrinsic compensation, then most of my paid employments have been largely leisure pursuits…. In between the extremes of subsistence work that is drudgery and leisure work for which one is paid, there lies a spectrum of occupations in which both aspects of work are found in varying degrees of admixture. My good fortune has been that I have had the opportunity to choose the occupations of my life so that they would be predominantly filled with leisure

Suppose that that had never happened. Suppose that after being graduated from college, I went to law school or into business. I might never had gone back to reading the great books again, under the illusion that I had mastered them in my first reading of them. After all, had I not graduated with honors? For all intents and purposes, was not my superior literacy confirmed by the high grades I received? In my first two years of reading the same books that I had read as a student with Erskine, but now reading them again in order to collaborate with Mark Van Doren to discuss them with our students, my eyes were opened to the fact that I had not understood them very well, if at all, on my first reading. In the next five or six years, that discovery was repeated again and again, as I learned more each time I reread the same books I had read before.

Now at the end of my life, still rereading the great books that I started reading seventy years ago, I can summarize this whole process by repeating two insights mentioned before in this book: (1) the great books are the books that are inexhaustibly rereadable for both intellectual pleasure and profit: (2) understanding the ideas to be found in the great books develops slowly in the course of one’s whole life, bearing its best fruits in one’s mature years after fifty or sixty. This does not complete my recollection of the wonderful seven years I spent co-moderating great books seminars with Mark Van Doren. I became close friends with Mark and his wife Dorothy, quite apart from our academic association as teachers. I gazed upon their two sons, Charles and John, when they were still in their cradles at the hospital in which they were born. Both Charles and John have been my friends ever since they have grown to manhood. Both have been my associates at the Institute for Philosophical Research, in editorial work for Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., and in the Paideia school reform project. I cannot recall all the details of that friendship with the Van Dorens while I was still living in New York and teaching at Columbia, and when I went on many visits to New York after I moved to Chicago. But bright in my memory is Scott Buchanan, whom I met at Columbia, whose first book Possibility was published by C. K. Ogden along with my first book Dialectic, and who later, after coming to the University of Chicago to work with Hutchins and me, became Dean of St. John’s College, and innovator of the New Program there. He and I were closely associated in our friendship with the Van Dorens. All of us spent our summers in Cornwall, Connecticut, where the Van Dorens had a house on one side of the valley, and where Scott and Miriam Buchanan had another house on the other side, which Helen, my first wife, and I shared. I recently found in my files two items that help to complete the picture of those years. They paint a portrait of me that is flattering to an embarrassing degree. I hope I can be forgiven the immodesty of quoting them here. I do so because I cannot myself remember the details of my behavior in the ambience of my relationship to the Van Dorens and the Buchanans.

Now at the end of my life, still rereading the great books that I started reading seventy years ago, I can summarize this whole process by repeating two insights mentioned before in this book: (1) the great books are the books that are inexhaustibly rereadable for both intellectual pleasure and profit: (2) understanding the ideas to be found in the great books develops slowly in the course of one’s whole life, bearing its best fruits in one’s mature years after fifty or sixty. This does not complete my recollection of the wonderful seven years I spent co-moderating great books seminars with Mark Van Doren. I became close friends with Mark and his wife Dorothy, quite apart from our academic association as teachers. I gazed upon their two sons, Charles and John, when they were still in their cradles at the hospital in which they were born. Both Charles and John have been my friends ever since they have grown to manhood. Both have been my associates at the Institute for Philosophical Research, in editorial work for Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., and in the Paideia school reform project. I cannot recall all the details of that friendship with the Van Dorens while I was still living in New York and teaching at Columbia, and when I went on many visits to New York after I moved to Chicago. But bright in my memory is Scott Buchanan, whom I met at Columbia, whose first book Possibility was published by C. K. Ogden along with my first book Dialectic, and who later, after coming to the University of Chicago to work with Hutchins and me, became Dean of St. John’s College, and innovator of the New Program there. He and I were closely associated in our friendship with the Van Dorens. All of us spent our summers in Cornwall, Connecticut, where the Van Dorens had a house on one side of the valley, and where Scott and Miriam Buchanan had another house on the other side, which Helen, my first wife, and I shared. I recently found in my files two items that help to complete the picture of those years. They paint a portrait of me that is flattering to an embarrassing degree. I hope I can be forgiven the immodesty of quoting them here. I do so because I cannot myself remember the details of my behavior in the ambience of my relationship to the Van Dorens and the Buchanans.

The first item is an excerpt from the Foreword written by Dorothy Van Doren to a collection of her husband Mark’s letters. It follows: Another friend with whom my husband corresponded was Mortimer Adler. Mark knew Adler slightly as a student, but shortly after Adler graduated, they shared a section of the General Honors course, the forerunner of the humanities series. Adler was lively, enormously energetic, a great talker, and incomparably intelligent. They had a great time together, and my husband felt that he had to work his hardest to keep up with this volatile, yet deadly serious student. In his Autobiography, Mark writes, “he would talk so fast that his tongue, as I told him, fell over itself.” Soon they began to see each other away from the university, and as with so many of Mark’s friends, the wives were included. After the General Honors class, on Wednesday evenings as I remember, I would meet the two men at the Adler apartment and Helen Adler would make muffins for us. I particularly remember the four flights of stairs I had to climb, as our son Charles was born that winter. My husband has always said that he learned everything he knew about philosophy from Adler and Buchanan, and a great deal from Adler about poetry, which Adler denies. At any rate, the friendship flourished for more than forty years.

The second item is an excerpt from a letter written by Mark Van Doren to his son John in 1946: I have been thinking over one part of your letter, the part about wise men, and have collected this thought about Mortimer [Adler]. He may not be wise, but he makes other men wise; he is almost the necessary condition for wisdom in others. They resist him, correct him, soften him, relax him, interpret him, and in the process feel superior to him; but there he is all the time, furiously thinking and speaking, and fanatically faithful to the truth-and that is precious too. He has amde Scott wiser-by reaction-than he was, and so I think with each of his friends. He is an angelic dope, and as such they worship him. They couldn’t do what he does even if they tried. Their wisdom has a negative feel when he’s around, as God’s does, maybe, when he contemplates the sons of men. He is greater than they, but only they could make him know it. This, I’m sure, is one reason he loves them. Or put it this way, Mortimer alone among the men we know is irreplaceable.

The second item is an excerpt from a letter written by Mark Van Doren to his son John in 1946: I have been thinking over one part of your letter, the part about wise men, and have collected this thought about Mortimer [Adler]. He may not be wise, but he makes other men wise; he is almost the necessary condition for wisdom in others. They resist him, correct him, soften him, relax him, interpret him, and in the process feel superior to him; but there he is all the time, furiously thinking and speaking, and fanatically faithful to the truth-and that is precious too. He has amde Scott wiser-by reaction-than he was, and so I think with each of his friends. He is an angelic dope, and as such they worship him. They couldn’t do what he does even if they tried. Their wisdom has a negative feel when he’s around, as God’s does, maybe, when he contemplates the sons of men. He is greater than they, but only they could make him know it. This, I’m sure, is one reason he loves them. Or put it this way, Mortimer alone among the men we know is irreplaceable.

The rest are more or less wise, but whatever he is, he is absolutely . . . As I now reread these two extracts, I can only say that I think William Wordsworth was wrong in that line of his about the Child being father of the Man; though I share the sentiment expressed in the two lines that follow: And I could wish my days to be bound each to each by natural piety.