Our “roundtable discussions” or, simply, “roundtables,” are conversations upon an agreed topic and take their initial direction from particular texts that have been read for that specific roundtable. We say “initial direction” as the conversations can go wherever the flow of ideas leads. The number of participants is usually limited to three or four people to allow for the presentation of differing viewpoints without the impediment of having so many voices that give and take among the participants becomes unwieldy.

Our “roundtable discussions” or, simply, “roundtables,” are conversations upon an agreed topic and take their initial direction from particular texts that have been read for that specific roundtable. We say “initial direction” as the conversations can go wherever the flow of ideas leads. The number of participants is usually limited to three or four people to allow for the presentation of differing viewpoints without the impediment of having so many voices that give and take among the participants becomes unwieldy.

The topic of this roundtable discussion is “Good and Evil.” The texts that served as the catalysts for the conversation are Frederich Nietzsche’s “Beyond Good and Evil” and Aristotle’s “Metaphysics,” Nicomachean Ethics,” and “Politics.” Here is a link to the roundtable.

The topic of this roundtable is “Is there an ideal size of human community?” Our texts for the roundtable were excerpts of Plato’s “Republic,” Aristotle’s “Politics,” and St. Augustine’s “City of God.” Here is the link.

This class recording features Dostoevsky’s “Brothers Karamazov.” The moderators for this class were Fr. Joseph Fessio, Mr. Patrick Carmack, and Mr. Steve Bertucci. Here is a link to the class.

by Patrick S.J. Carmack

Anytime available for leisure is a good time to begin or resume the study of great books. However, for young people who have never studied them, two limitations frame the answer to the question: when is the ideal time to begin the study of the Great Books? The first is a limitation intrinsic to the student, the second extrinsic:

1.) The student must be able to read reasonably well, and ideally should also be able to write, speak and listen well. In other words, a Great Books student should have completed the study of the trivium–the elemental liberal arts–and so know how to read, write, speak and listen well. I would add to those arts the ability to use a personal computer to locate and read the various texts and commentaries and to write and submit essays online. Given that these learning arts are typically taught in the elementary grades (1st-8th), the study of the Great Books logically should follow sometime after completion of 8th grade—primary education.

2.) The other limit is imposed by factors extrinsic to the student: the responsibilities and financial pressures of rising college costs, housing, student loan debt, costly auto and health insurance, marriage and parenthood, effectively end the availability of sufficient leisure time and financial resources necessary for formal, liberal educational opportunities for most college-age students. By that age students are under increasing pressure to complete some specialized, vocational or professional education in order to generate an income to fulfill those responsibilities and limit their debts.

The conclusion is that—ideally—Great Books education should begin after the first eight years of primary education, during the whole of secondary education—the four high school years. For most students this means beginning the study of the Great Books in 9th grade (14 year olds) or after, and continuing at least through 12th grade (18 year olds or so).

In the United States the high school years at schools are too often an intellectual wasteland, as most high school graduates would readily attest, which needlessly protract study of the trivium which has been expanded into secondary education due to our remarkably ineffective public (and most private) elementary school education. This is supplemented with thin-to-bad literature selections (such as much of that proposed by Common Core), with much time wasted on dubious social engineering materials and insipid textbooks designed by large publishing houses for the “average” student. Dr. Adler:

“As far as the United States is concerned, the reorganization of the educational system would make it possible for the system to make its contribution to the liberal education of the young by the time they reached the age of eighteen…The tremendous waste of time in the American educational system must result in part from the fact that there is so much time to waste.”

Many years ago–from the Middle Ages to the last century–the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree signified completion of the secondary level of education (following the elementary, grammar or primary level) and so readiness to enter into the third level of formal education – the university, for specialization in one’s chosen field. With that background in mind Dr. Adler wrote:

“If I had any hope that in the foreseeable future, the educational system of this country could be so radically transformed that the basic liberal training would be adequately accomplished in the secondary

Renowned philosopher Jacques Maritain held virtually the identical view as Dr. Adler: “I advance the opinion, incidentally, that, in the general educational scheme, it would be advantageous to hurry the four years of college, so that the period of undergraduate studies would extend from sixteen to nineteen. The B.A. would be awarded at the end of the college years [thus at 19 years of age], as crowning the humanities…” Their view of completing generalist, liberal education by age 18-19 is nothing new in this country.

In colonial America, before entering school at the age of fourteen or fifteen, students were expected to be able to speak Latin, and in college they were fined for not speaking in Latin, except during recreation. Latin was the language of most of their textbooks and lectures. Knowledge of New Testament Greek was required for admission, and students also studied Homer and Longinus in Greek. In Latin the chief authors were Cicero, Virgil, and Horace. A lifelong interest in the classics was common. “Every accomplished gentleman,” says Wertenbaker, “was supposed to know his Homer and his Ovid, and in conversation was put to shame if he failed to recognize a quotation from either.” Self-made men, like Benjamin Franklin, without the benefit of college, derived more from the ancient world than one would expect, but the more typical Founding Fathers meditated long and deeply on the ancient patterns of democracy and republics, and Jefferson was only expressing a frequent view of his time when he said of ancient literature: “The Greeks and Romans have left us the present models which exist of fine composition whether we examine them as works of reason, or style, or fancy… To read the Latin and Greek authors in the original is a sublime luxury.” The history, philosophy, and literature of the ancients did not seem remote or antiquated, but intimately present because permanently enlightening.

In the Harvard Classics, Harvard President Dr. Charles Eliot prepared a selection of 60 readings from that great books set to provide a “pleasant introduction” to it for students ranging in age from 12 to 18, and stated “There is no place where the Harvard Classics find greater usefulness than to children [referring to the same 12-18 year old readers]. If you have children in your family… let them have free access to the Harvard Classics [which] will bring to the growing boy and girl a familiarity with the supreme literature, at the impressionable age when cultural habits are formed for a lifetime.”

Scientific research strongly supports Dr. Eliot’s opinion. In a study published in the Journal of Philosophy in Schools (2015) several faculty members from Sam Houston State University in Texas decided to replicate a 2007 study conducted in Scotland on the effects of a philosophy for children program. Philosophical works are a large component of Great Books courses. The original study was one of few randomized, controlled clinical trials assessing the impact of a philosophy for children program. It showed significant gains in cognitive abilities by children who participated in weekly philosophical group discussions.

This new study found that the seventh-grade students who had experienced the philosophy for children program showed significant gains relative to those in the seventh-grade control group, providing evidence for the main contentions of the original 2007 study — namely, that “regular, one hour per week, structured community of inquiry philosophy for children sessions are a relatively powerful educational intervention which boosts students’ cognitive abilities significantly while doing so at a very small cost both in materials needed and in instructional time.”

Another study by Durham University in the United Kingdom further strengthens the case for philosophy for children and provides evidence for its efficacy as an intervention in closing the achievement gap. This study, which included more than 3,000 students in 48 public primary schools across England evaluated January-December, 2013, found that “pupils’ ability in reading and math scores improved by an average of two months over a year,” but, more importantly, that the “disadvantaged pupils in the trial, those on free school meals, saw their reading skills improve by four months, their math by three months and their writing ability by two months.”

Nobel Prize-winning University of Chicago economist Gary S. Becker made much the same point about the importance of early education when he noted the effect of the lack thereof in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution in the United States, in which too many children are neither learning the skills nor adopting the habits and values that other children acquire. One result is increasing income inequality. For example, prior to 1950, college graduates earned about 40 percent more than high school graduates, on the average. Today they earn 80 percent more. Thus education prior to college admittance age (roughly age 18) is increasingly important in our society. When is it too late to make up for deficient early education? Becker says studies show that government job-training programs for 16-year-olds do not succeed because they cannot overcome the failure to learn skills in their first 16 years.

Can government schools solve the problem by providing education and skills that traditionally have been provided by parents? Becker, citing various studies, concludes there is no evidence government schools can solve the problem. What about replacing real mothers with professional day care personnel? Sweden tried that on a grand scale—a literal, Spartan-like nationalization of the family—at great social cost, but found no evidence of positive effects on children. Early home education in the liberal arts, complimented at the secondary level with general liberal education in the humanities such as contained in the Great Books, offers a well-tested, traditional solution to the current educational crisis. As schools in general do not offer such an education at the secondary level, it is left for home educators to find ways to provide this for their students.

Adler had great respect for the potentialities of the minds of teenagers, and did not want to see those formative years wasted, entailing the risk of losing the opportunity for liberal education altogether, which is so often the case. In a 1970 appearance on the TV show Firing Line, hosted by William F. Buckley, Jr, Adler made the point that liberal education, the backbone of which is study of the Great Books (rather than a disorganized, smorgasbord of electives), should be completed by the end of secondary (high) school:

“I think the liberal arts degree is given four years too late. I would take American schooling and cut it down, and make it European in this sense: six years of elementary schooling; six years of secondary (lycee, gymnasium – high school); the collegiate degree (i.e., the Bachelor of Arts) coming at the end of that [i.e., at the conclusion of secondary/high school education – 12th grade in the US]…I might extend that by taking [into account] the differences in the population: I might have the very brightest twelve years [i.e., through 12th grade]; for the next level thirteen years; and the last, fourteen years, but not more than fourteen.”

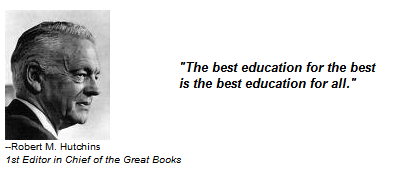

That was Adler’s view in 1970, after spearheading the Great Books Movement, with Robert Hutchins, President of the University of Chicago, for half a century. For the next three decades until his death in 2001, Adler’s view did not change, rather it was repeatedly confirmed. In 1983 Adler wrote: “I have been conducting seminars for 60 years now, with students in high schools and colleges and with adults who have engaged in the reading and discussion of great books or who have been participants in the Aspen Executive Seminars. Long experience has convinced me that seminar teaching, on the Greek or Socratic model, not the German one, belongs not only in the colleges, but should be carried on also in high schools, where students have proved every bit as able to profit from seminars that I have conducted as have their college counterparts–have shown themselves even better participants in some ways.”

Three years later, in 1986 Alder again wrote: “Ideally, everyone should be both a generalist and a specialist–a generalist first at the level of basic schooling…Schooling from kindergarten through 12th grade would initiate the young in the process of acquiring general, liberal, and humanistic learning. The colleges and universities to which some of them then went would afford them opportunity for specialization in a field or fields that they elected to pursue.”

Seven years later, in 1990 Adler reaffirmed his consistent view that the Great Books should be studied in the high school years, “before age eighteen.” In a talk to the National Press Club on October 30th that same year, Alder made it clear that even 16-year- olds were quite able to complete a four-year program of study of the Great Books: “I wanted to have graduation from high school at age 16, not 18.”

In 1992 he wrote: “I even went so far as to suggest that the B.A. degree be given on graduation from high school, signifying the completion of the first stage of general education, and that undergraduate colleges becomes three-year institutions, giving the M.A., or some similar degree, for the completion of the specialized course, with a little general education retained as a carry-over from high school…If high school were completed at age sixteen instead of eighteen, then I proposed that, in the next two year , there should be compulsory nonschooling…as a result of two years of work experience, either in private or the public sector of the economy…they would be better students in college, because they would be more mature; and they would have a better sense of what they wanted to do with their lives.”

What about those who were unable to obtain a liberal education in high school? In 1992 Adler wrote that taking up the study of the great books after specialization in college was the next best alternative: “If future citizens were to be given that kind of education, which I thought prerequisite for the intelligent discharge of their civic duties, then that would have to be done before they went to college, or after they graduated from college, or better, at both times of their lives.”

This will doubtless raise the question in some minds as to whether, if one missed the opportunity in high school or homeschool, one ought to study the Great Books in a liberal arts or Great Books college program. The answer is certainly yes, to which the demand for Great Books college education, testified to by the growth and spread of Great Books colleges and Great Books college programs, such as at Columbia University, The University of Chicago, St. John’s College (Annapolis and Santa Fe), St. Mary’s College (Morgana, CA), Thomas Aquinas College (Santa Paula, CA), Gutenberg College (Salem, OR), Notre Dame’s Great Books Honors program, and at many other colleges and universities, gives eloquent testimony.

However, the vast majority of the 4,500 or so US colleges and universities do not offer a Great Books program, and while the list that do—at least in some fashion (from one or two courses up to four-year programs)—has grown to over 100 (see the Appendix for the list of these), that still represents only about 2% of the total number of colleges and universities in the US. Another 10% or so of tertiary institutions are liberal arts colleges, in varying degrees, but do not offer Great Books programs. Thus Adler’s advice above, to study the Great Books either before or after college, or both, remains relevant for the great majority of students, including his consistent advice to begin such study during the high school years, if possible, for the several reasons mentioned.

Three FAQ (discussed in order, following)

• Are the Great Books too difficult to be mastered by teenagers?

• Would the study of a small number of Great Books be sufficient for such an educational approach?

• If a student begins a Great Books program, what should the accompanying curriculum in other subjects look like?

1.) Are the Great Books too difficult to be mastered by teenagers?

Yes, they are too difficult to be mastered by young students. But that is beside the point—no high school, college or university student can “master,” plumb the depths nor exhaust the Great Books– that is the work of a lifetime. The error implicit in this objection is that schooling and education are synonymous, and that therefor mastering material–certainly one goal of education—must therefore take place at some point during formal education. Adler addressed this objection as follows:

“No one can become an educated person in school, even in the best of schools or with the most competent schooling. Schooling is only the first phase in the process of becoming educated, not the termination of it.” Education should not be identified with schooling. Rightly conceived, education is the process of a lifetime, and schooling, however extensive, is only the beginning of anyone’s education, to be completed, not by attendance at educational institutions in adult years, but rather by the continuation in learning through a wide variety of means during the whole of adult life. Hutchins put it well: “The college graduate is presented with a sheepskin to cover his intellectual nakedness.” Schooling can and should be terminated at a certain time, but education itself cannot be terminated short of the grave

If mastering the Great Books is beyond the ability of young students, what then is the point of studying them in high school or college? Stringfellow Barr, co-founder of the Great Books program at St. John’s College, Annapolis, responded to that question by saying that the students in the program were not expected to master the great books; few if any adults could be expected to do that. At St. John’s, he said, “the great books serve the purpose of a very large bone thrown to a young puppy. The puppy will wrestle with it, will probably not get much meat off it while agitating it, but will certainly sharpen its teeth in the process.”

Jacques Maritain makes the same point with a like metaphor: “One cannot emphasize too much the educational role of the great books. Yet this role does not only consist in sharpening the intellectual power of the youth; they are not only like a large bone with which a puppy struggles so that his teeth may grow sharper. To bring the metaphor to completion, it should be added that this large bone is a marrow-bone, and that not only do the puppy’s teeth have to grow sharper, but his living substance also has to feed itself upon the valuable marrow. It is doubtless not a question for the young student of “mastering” the great books, but of discovering and being quickened and delighted by the truth and beauty they convey—and, if they convey errors too, of discerning and judging the latter, however awkward and imperfect this process may be at first. The intellect’s teeth are not really sharpened if they are not able to separate the true from the false.”

While mastery of the great books is beyond them, Adler noted that high school “students have proved every bit as able to profit from seminars that I have conducted as have their college counterparts–have shown themselves even better participants in some ways.” Again, “In 1933-34, Bob Hutchins and I undertook to read the great books with a selected group of juniors and seniors in the University [of Chicago] high school. Though younger than the students in our General Honors course in the college, the high school students did just as well; in fact, having had less schooling, they were somewhat less inhibited in discussion.”

It is the experience of the author, after conducting many great books seminars over the years and sharing notes with other Great Books moderators (or tutors, as they are often called), that high school-age students are generally more open and eager to consider the ideas and insights, and to accepting the occasional wisdom contained in the Great Books, while at the same time are not burdened with the radical skepticism that plagues our educational system which is inculcated in young minds by the radical skepticism and post-modern nihilism that plagues our higher educational system and which is inculcated in young minds by those schools and media. In other words, they generally still believe truth exists and can be known, and so generally make better students in Great Books programs than older students.

In 1986 Adler conducted five seminars in Chapel Hill, North Carolina for 20 students from Millbrook High School in nearby Raleigh. His experience there further confirmed his belief in the beneficial effects on high school-age students of studying the Great Books. The seminars were recorded and are still available. The Great Books texts discussed in the five sessions from Monday to Friday were: Plato’s Apology, in which Socrates defended himself at his trial in Athens; the first eight chapters of Book I of Aristotle’s Politics together with the first book of Rousseau’s The Social Contract; Machiavelli’s The Prince; the Declaration of Independence; and Sophocles’ Antigone. Adler described the experience:

“The seniors from Millbrook High School had never read any of these texts before and had never been in seminars in which texts they had read were discussed. Everyone agreed, both the students who participated in the seminars and the teachers who observed them, that the progress was remarkable—a progress that is visible to anyone who watches the five videotapes in succession.

Given this visible evidence of extraordinary progress in the growth of understanding, I asked my audiences to imagine what the results might be if, instead of just five days in their senior year of high school, these same students had had seminars once a week throughout all four years of high school; or, going further, I asked them if they could imagine that these same students had had seminars once a week from the third grade on to the twelfth. I told them they would fail because, I said, that result would be unimaginable. It would be beyond their fondest dreams.

One other insight emerged from the Millbrook seminars. The seminars did more for the students than increase their understanding of basic ideas and issues. They clearly improved the students’ skills in reading, speaking, and listening. Most of all they clearly had an extraordinary effect on their ability to think critically, a skill that cannot be taught in itself or in a vacuum, but only in the context of discussions that involved reading, speaking, and listening.

Van Langston, the principle of Millbrook High School, accompanied his students on the bus in their hour’s ride from Raleigh to Chapel Hill and back. I repeated something that he told me at the end of the week. He had been acquainted with these students for four years and, in his experience with them, they had never been found discussing anything but games, frivolities, making money, recreation of all sorts. But in the bus returning to Raleigh from Chapel Hill each afternoon after the seminar was over, they engaged in agitated discussion of ideas and issues with which they had been confronted in the seminars.”

One final observation on this question: despite his later intellectual accomplishments, Adler was himself as a high school drop-out. At age fifteen he read the autobiography of John Stuart Mill, who though entirely unschooled (not uneducated) had read many of the great books in the Western tradition before the age of eleven. When he read Mill had read the Platonic dialogues by age five, Adler had to read them! There Alder discovered his lifelong hero, Socrates. Lacking a high school diploma, young Adler nevertheless managed to get into Columbia College where he began the study of the Great Books. This personal experience of what was possible for young intellects, even though unschooled as Mill was, or a high school drop-out as Adler was, convinced him never to underestimate the learning capacity of young minds, as his later experiences—some recounted above—confirmed, many times, over the next eight decades of his life.

2.) Would a small number of Great Books be sufficient, perhaps better, for such an educational approach?

What of the objection that a reading and discussion program introducing one book (or major excerpt) a week, 120 or so over four years, cannot serve as more than an introductory or survey course in the classics, which should be read much more carefully—only a few a year—and more in depth rather than for breadth?

Among those who promote the study of the Great Books there has been some debate regarding the ideal number of Great Books to be read in a year, or more, and the time which should be devoted to their study. As noted above, Dr. Adler and Jacques Maritain believed the four high school years should be largely devoted to the study of great books, and our extensive experience with four year programs over the last 15 years strongly supports that view.

Studying a handful of Great Books in one semester, or in two or even six semesters does not allow sufficient time to accomplish the purpose of acquainting the students with enough of the Great Books to give them a sense of their full range and scope. Of course there is nothing magical about a four year program, but besides offering the opportunity of at least acquainting the students with 120 or so of the Great Books and the great ideas contained therein, there is something quite practical about it as well: compulsory schooling in the US is widely set at 12 years and most, or at least many, students have learned the basic liberal arts by the completion of 8th grade, leaving 9th to 12th grades available for applying those learning arts to something – the best something being Great Books. We have found four years reasonably sufficient for that purpose.

In four years a Great Books program may be divided into what has become a more or less standard, chronological sequence of the ancient Greek, Roman, Medieval and Modern Great Books, each studied for an academic year of two semesters. Studying about 30 books from each roughly 400 year time-period, in chronological order, gives students a broad and substantial exposure to the intellectual life of each period, to the great ideas discussed in them, and to that portion of the Great Conversation—the ongoing intellectual dialogue of Western civilization contained in the Great Books—written in each period.

To reduce the number of books significantly would break the thread of the Great Conversation which requires—at its best—representative works connecting great books discussing the great ideas contained in them, without skipping any lengthy period of time in which they were further discussed and developed, from Homer to the present. As stated above, even four years is not sufficient time for an in depth study of the Great Books, but neither is the whole time of formal education sufficient–-that is the work of a lifetime. “The object of education is to prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives.” –Robert M. Hutchins

To reduce the number of books significantly would break the thread of the Great Conversation which requires—at its best—representative works connecting great books discussing the great ideas contained in them, without skipping any lengthy period of time in which they were further discussed and developed, from Homer to the present. As stated above, even four years is not sufficient time for an in depth study of the Great Books, but neither is the whole time of formal education sufficient–-that is the work of a lifetime. “The object of education is to prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives.” –Robert M. Hutchins

It may be objected that there are such gaps even when selecting 120 or so great books for a four year program, which is true. However, if each of the Great Books selected included the thoughts of the authors of the Great Books for a like number of years, each of the 120 books selected would only need to cover 23 years to total to the 2,750 or so years from Homer to the present. This is much too arithmetic and simple of an analysis solely to rely upon, for any purpose, to be sure. But the point remains that a four year program can at least acquaint students broadly, and chronologically, in the order of discovery, with virtually the whole range of the history of thought and intellectual activity in Western civilization, and the various fields and principal authors and great ideas included—oftentimes exposing them to whole areas of thought and knowledge about which they were previously unfamiliar.

It is a uniform experience in Great Books programs of significant length, that a number of students previously aiming at trades, business, engineering, or law, shift their interests to literature, philosophy, history, political science or other of the humanities. That is not the goal of great books programs, it is however an inevitable effect of broadening horizons and opening minds to new possibilities either not previously considered or insufficiently considered and undervalued in and by our educational system.

Too often schools educate to serve the narrow interests of for-profit enterprises eager for narrowly trained workers useful for short range purposes, who in a few short years are often left unemployed due to learning only a few limited skills made obsolete by the rapid pace of technological innovation. A broad, liberal education can give them skills and knowledge necessary to be able to adapt to rapid change and a wide variety of challenges.

“Education is not to reform students or amuse them or to make them expert technicians. It is to unsettle their minds, widen their horizons, inflame their intellects, teach them to think straight, if possible.” –Robert M. Hutchins

That being so, it is obvious a program could nevertheless attempt to cover too many books, even if the main purpose is simply familiarity and introduction. Maritain warned of this: “That is why the great books should not be too many in number, and their reading should be accompanied by enlightenment about their historical context and by courses on the subject matter.” This caveat was in the context of praising and agreeing with Adler’s promotion of the study of the Great Books a la’ Erskine’s approach at Columbia University, which involved the study of roughly one book per week. That one-book-a-week approach and approximate pace is used in most four-year Great Books programs. Of course one key reason is that, with some exceptions, it is possible, and very practicable, for high schoolers, and up, to read one book a week during the academic year. Decades of experience have proven this.

What about really difficult works, such as Aristotle’s? In every Great Books program, more difficult works, those that it would be too much to expect young students to read in a week, are either broken into two or more weeks of reading, or only important, major excerpts are read. Additionally, in most cases the most difficult works (usually philosophy or the natural sciences) fall into the Modern period, and so are read by students in the later or fourth year of the program (if a four year program), when they are much better readers, long experienced in reading books of all kinds.

Of course what this means over the four years of high school or undergraduate college is that approximately 120 great books or major excerpts are read during a typical four-year great books program. Shorter great books programs reduce the number accordingly.

When one gets beyond the rather generic title “Great Books” one can begin to see the advantages of Erskine’s and Adler’s approach of one book per week. It is difficult to reduce and prioritize the works in the various sets of great books (e.g., Britannica’s Great Books of the Western World includes 517 works) to 120 or so. Perusing a typical four-year Great Books Program reading list will give the reader some idea of the difficulty, and loss, in further reducing the list (to shorten it, should one leave out Homer, or Moses, Plato, Virgil, Augustine, Aquinas, Chaucer, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Darwin, Freud, Einstein, or the like ?). Is a student who has never read, perhaps never even heard of, such great works truly educated or prepared to become so? The compulsory high school years of education (or undergraduate education) typically last four years, hence the logic of using all four of them most wisely, studying the works of the wise, and not wasting them on mediocre, or worse, materials.

3.) If a student begins a Great Books program, what should the accompanying curriculum in other subjects look like?

The primary grades (usually k-8 in the US) are intended to instruct the students in the elements, or grammars, of the liberal arts (hence we refer to them as elementary or grammar schools)–the learning arts–so that they possess for themselves the tools of learning. We will discuss elsewhere what those tools are, but they include the arts of reading, writing, speaking, listening, and calculating, sometimes summed up as the 3 R’s (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic [or reckoning]). If that goal is accomplished reasonably well, that leaves the four traditional high school years (9th-12th grades) for applying those newly-learned liberal arts to gaining a liberal, generalist education by studying proper materials. The learning or liberal arts understood in the strict sense are only a part—the first part—of a liberal or generalist education.

A student who has learned only the liberal arts (think the 3 Rs) but has never applied them to excellent material for study (such as the Great Books), would know how to read, write, speak, listen and calculate, but neither what to write about nor why to do so. It’s more than semantics: the liberal or learning arts are just as necessary for vocational, professional or specialized learning today as they are for a generalist education–everyone in modern society needs to know how to read, write, speak, listen and calculate. The key difference is whether, before specialization occurs, they first have the opportunity to apply those arts to a broad range of material selected for the specific purpose of gaining a liberal education in the full, generalist sense of the term. If not, then they may have learned the liberal arts, in the strict sense, but are not liberally educated, at least not fully so. As Hutchins put it, “they will have escaped illiteracy without ever achieving true mental cultivation.”

Regarding the first twelve years of education Adler wrote: “All normal human beings should have the same basic schooling for twelve years.” “I think the curriculum for liberal studies should be completely fixed. There should be no electives at all. I do not think the student is in any position to make choices about what he should study. I do not think his interests make any difference. They are all human beings; they are all going to become citizens; they are all going to have lots of free time. I think electives–the choice of specialization–should come after the liberal arts degree.

To the criticism that a completely required curriculum imposes too much discipline and reduces freedom, Stringfellow Barr replied by reminding the critics that the undirected often suffers a worse fate than a loss of freedom. The ship that will not answer to the rudder, he remarked, must answer to the rock.

In another article we will examine the specific, fixed courses Adler and other reformers recommend to accompany Great Books courses. The reader may find interesting Adler’s suggestion regarding taking a break from formal education in the time after completion of liberal education and before specialization (so after high school in his ideal model):

“There should be a hiatus [from school] of at least two years–I would prefer four…[students] certainly cannot become mature as long as they remain in school; on the contrary, they suffer from prolonged adolescence. That is a pathological condition which can be prevented only by getting the young out of school as soon after the onset of puberty as possible.”

To summarize Dr. Adler’s views on the questions posed in this chapter: he strongly believed in beginning a four-year, liberal education including, as the most important and central part, weekly Great Books seminars, in secondary education, to be completed by age 18, which closely accords with Maritain’s view of conducting high school liberal education including the study of the Great Books in the four years from age 16 to 19. Both philosophers believe completion of such a secondary/high school, generalist education would merit the award of a Bachelor of Arts degree, freeing subsequent tertiary education at U.S. colleges and universities, and the time and treasure spent there, for specialization.

![Dr. Mortimer Adler [sitting] at his last Great Books Discussion Group, (2000 A.D.), with the initial online Great Books Program directors [standing, left to right] Steve Bertucci, Pat Carmack (the author), and Tom Orr](http://www.angelicum.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/pat.jpg)

Dr. Mortimer Adler [sitting] at his last Great Books Discussion Group,

(2000 A.D.), with the initial online Great Books Program directors

[standing, left to right] Steve Bertucci, Pat Carmack (the author), Tom Orr

The rapid expansion of dual enrollment high school/college courses, early college courses, and similar use of Advanced Placement, Advanced Standing, CLEP, IB, and ACE college credit recommendations, for which high school, homeschool, or independent students can earn college credits for completing courses and/or tests of college level content and rigor, confirm Alder’s and Maritain’s esteem for the learning capacity of teenage minds and what they can achieve with the best educational opportunities and materials. All of these hybrid courses also serve to reduce the financial burden of endlessly increasing college costs, as they are generally available for a fraction of the cost of regular college tuition, room and board.

Online Great Books Programs, since they are not limited by classroom size, enable potentially limitless numbers of students the opportunity to gain a broad, liberal education in the humanities through the study of the greatest books of Western civilization, while in high school or home school (and older as well), via distance education, for personal growth, and for college credit.

Copyright 2015 All Rights Reserved by Patrick S.J. Carmack, J.D.

Footnotes omitted

What Happened to the Great Ideas? by John Berlau

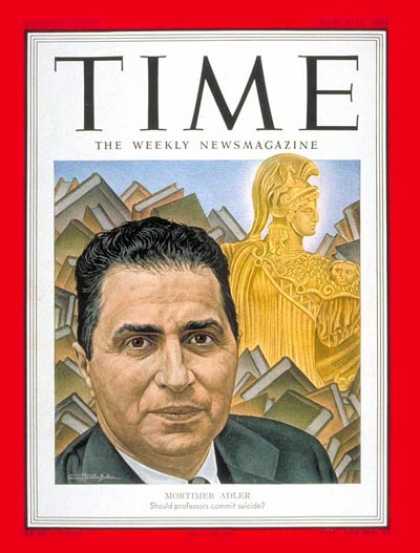

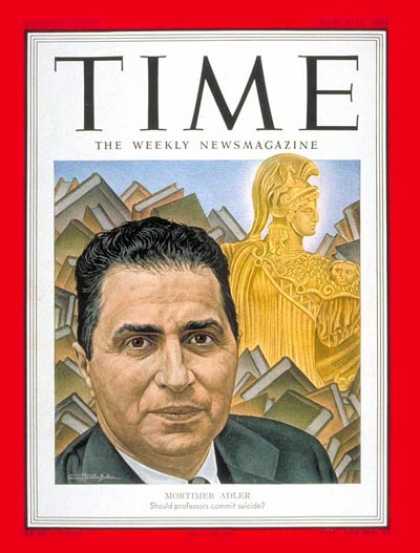

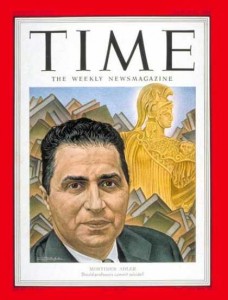

The following article has been reprinted with the kind permission of Insight Magazine and was originally published in August, 2001. The article briefly summarizes the life, work, and genius of Mortimer J. Adler, and discusses the profound influence he has made on education. Dr. Adler converted to Catholicism in the late years of his long life.

The following article has been reprinted with the kind permission of Insight Magazine and was originally published in August, 2001. The article briefly summarizes the life, work, and genius of Mortimer J. Adler, and discusses the profound influence he has made on education. Dr. Adler converted to Catholicism in the late years of his long life.

By John Berlau

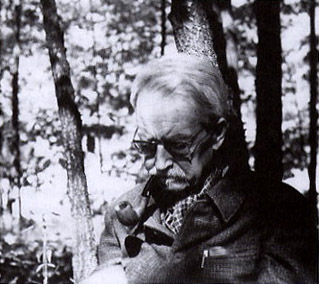

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler recently passed away, but his legacy lives on in the Great Books programs he inspired and succeeded in establishing across the nation.

Mortimer J. Adler died in late June at the age of 98. Born in 1902, he was a philosopher and educator who lived through almost every year of the 20th century. But he was not a man of that century, at least not in establishment academic circles.

From the 1920s until his death, Adler most often was a voice in the wilderness crying out against educational trends he saw as destructive. He fought progressive education’s child-centered academic curriculum and vocation-centered training. Instead he championed general education in the classics. At a time when moral relativism has become dominant, Adler proclaimed that there still were universal moral truths to be found in the works of Plato and Aristotle.

Academics heaped scorn on him for writing about philosophy in simple terms for the masses in books with titles such as Ten Philosophical Mistakes and Six Great Ideas and Aristotle for Everybody: Difficult Thought Made Easy. He would maintain throughout his life that philosophy is everybody’s business.

Adler was dubbed the Lawrence Welk of the philosophy trade by one critic. Dwight MacDonald of the New Yorker derisively referred to Adler’s work as The Handy Key to Kulture. In the 1990s, when Adler and his colleagues released a revised edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica’s Great Books of the Western World, he was attacked viciously because the series contained few works by women and none from blacks. Harvard University’s Henry Louis Gates blasted the Great Books for showing profound disrespect for the intellectual capacities of people of color red, brown or yellow.

Adler calmly explained that the authors were chosen not because they were dead white males but because their work had stood the test of time. He noted that the guidebook for the series recommended many good books by blacks and women, as well as works by white male authors that didn’t make the cut. But a Great Book must be relevant to human problems in every century, not just germane to current 20th century problems, Adler wrote. The educational purpose of the Great Books is not to study Western civilization, Adler explained in the 1970s. Its aim is not to acquire knowledge of historical facts. It is rather to understand the great ideas.

Even in death, Adler still may be an outcast in academia, but he inspired legions of followers who have formed colleges, homeschooling cooperatives and Great Books discussion groups in major cities based on his ideas about education. And although his political positions often were of the left he once advocated socialism and world government some of his biggest champions today come from the political right.

The Great Books are alive and well as a powerful approach to education, Stephen Balch, president of the conservative National Association of Scholars, a group that pushes for a core curriculum of Western classics, tells Insight. It’s alive and well in large part because of his efforts as the architect of this kind of grand design for education. Those who favor an education in the service of civilization are in his debt for all the work he did over the years to establish the Great Books model and to bring the Great Books to the American population generally, not just those at colleges and universities. He certainly wanted as many people to read the Great Books as possible, based on a belief that they did speak to everybody.

The Great Books are alive and well as a powerful approach to education, Stephen Balch, president of the conservative National Association of Scholars, a group that pushes for a core curriculum of Western classics, tells Insight. It’s alive and well in large part because of his efforts as the architect of this kind of grand design for education. Those who favor an education in the service of civilization are in his debt for all the work he did over the years to establish the Great Books model and to bring the Great Books to the American population generally, not just those at colleges and universities. He certainly wanted as many people to read the Great Books as possible, based on a belief that they did speak to everybody.

Longtime conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly credits Adler with championing an education in Western classics to everyone, against the progressive educators who thought the classics were irrelevant to many students. Progressive educator John Dewey didn’t believe in individuals excelling in knowledge, Schlafly tells Insight. He believed that the purpose of education was to socialize people and have them do what they re told, and Adler was a good counterbalance to that.

In the early 1980s, Adler and his colleagues set forth a detailed program of primary schooling called Paideia , which is the Greek word for the upbringing of children. In his book The Paideia Proposal, Adler proposed that the education for all children must be general and liberal and nonspecialized and nonvocational, no matter the perceived intellectual capacity of the child. Using milk containers as an analogy, he said the half-pint container as well as the gallon container should be filled to the brim with the same quality of substance cream of the highest attainable quality for all, not skimmed milk for some and cream for others. Adler also emphasized that as much as possible the great works should be taught in the Socratic method, in which children discuss what they have read, rather than as a top-down lecture.

Today, the Paideia Group Inc. consults with schools wanting to set up programs. Adler, who was honorary chairman, sometimes would go in and lead the children of participating schools in discussions. I have such wonderful letters from students who have been in the seminars thanking Mortimer for what it has done for their lives, Paideia Group President Patricia Weiss tells Insight.

The Paideia Group concentrates on public schools, Weiss says, because Adler was such a strong advocate of universal public education. Still, she says, public schools often are resistant to change. She hopes that charter schools will give teachers and parents more flexibility to implement Paideia.

Meanwhile, the Great Books curriculum really is taking off in homeschooling. Patrick Carmack, who homeschools his children in Colorado, cofounded the Great Books Academy after reading Adler’s books on education in 1999. The program assigns Great Books for participating children to read and holds online Socratic discussion groups in the style that Adler proposed. The directors met with Adler in 2000, and his longtime colleague Max Weismann serves as chairman. Carmack says the curriculum is being used by parents in every state and internationally.

At the college level, St. John’s College offers a four-year nonelective Great Books program that Adler helped design in the 1930s. The college, which has campuses in Annapolis, Md., and Santa Fe, N.M., uses no textbooks, at Adler’s prompting. The only texts are the primary materials that students read and discuss. Textbooks merely are catalogs of information that essentially are undiscussable, Adler wrote.

At Wright College, a community college in Chicago, Bruce Gans started a Great Books elective course in which one-fifth of the student body now has enrolled. Gans faced objections from other faculty that works by dead white males wouldn’t go over well with their mostly black and Hispanic students going to school while working. But he tells Insight that every year he gets letters and notes on the final exams from such students saying how much reading the great works has bettered their lives.

Adler maintained that schooling did not make one educated; it merely prepared students for a life of learning. No one can be an educated person, while immature, Adler wrote in The Paideia Proposal. Only through the trials of adult life, only with the range and depth of experience that makes for maturity, can human beings become educated persons.

Adler himself knew the value of self-education. Hoping to be a journalist, he dropped out of school at 14 to become a copyboy at the New York Sun. After a year, he took night classes at Columbia University to improve his writing. Reading the autobiography of English philosopher John Stuart Mill for a class, he discovered that Mill had read Plato at age 5. He felt a sense of shame that he had not yet done so and borrowed Plato’s works from a neighbor. Adler was hooked, and he eventually got a scholarship to study philosophy at Columbia.

Adler’s experience in the working world led him to propose a mandatory two-year hiatus from all schooling after students graduated from high school, although this was not formally included in the Paideia plan. Only after experience in life and work would students really be eager to learn. Young people certainly cannot become mature as long as they remain in school; on the contrary, they suffer from prolonged adolescence, Adler wrote in his autobiography Philosopher At Large. That is a pathological condition which can be prevented only by getting the young out of school as soon after the onset of puberty as possible.

This way, Adler said, universities would be populated with students who return to educational institutions because they have a genuine desire for further formal study, instead of students who occupy space in our higher institutions as the result of social pressures. Regardless of whether a person went to college, Adler maintained that lifelong learning was essential for personal happiness. Adler defined happiness as Aristotle did, not as instant pleasures but the joy and satisfaction that comes from living a virtuous life. He never stopped learning and wrote more than 20 books after he turned 70. The loss of immediate or short-term memory that inevitably accompanies advancing years in no way diminishes the power of creative, analytic and reflective thought, Adler wrote in his second autobiography, A Second Look in the Rearview Mirror, published when he was 89.

Some say the example of Adler’s long life of learning may itself be one of his most enduring legacies. Half-jokingly, Balch says, Mortimer Adler is a great advertisement about the longevity you can attain reading Great Books. You have so many of these big challenging books to read that you ve got to live a long time to do them justice.

Reprinted with permission of Insight. Copyright 2001 News World Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

THE BLESSINGS OF GOOD FORTUNE by MORTIMER ADLER

THE BLESSINGS OF GOOD FORTUNE by MORTIMER ADLER

Early in life I learned a lesson from Aristotle. Whether or not we succeed in having lived a good life is not entirely a matter of free choice and moral virtue. Virtue is certainly a necessary condition; it may even be the most important factor; but by itself it is not sufficient. The other necessary, but also insufficient, condition is having good fortune. Fortune, good or bad, plays a part in everyone’s life. The accidents of fortune are the things that happen to you. When good luck happens, you may aid and abet it by seizing the opportunities it affords, but its happening to you is beyond your control. The only things entirely within your own power are the things you freely choose to do, and even some of these require attendant good fortune for them to be fully achieved.

You may take care of your health by virtuous conduct on your part, but your achievement of a healthy body may also require a healthy environment, which may or may not be your good fortune to enjoy. (In my youth, I went through serious influenza and poliomyelitis epidemics unharmed. Through diligent care by my parents I escaped being ill but, that was still a blessing of good fortune.) In a book in which I have recited the free choices I made to devote myself to teaching and learning, to writing books and editing them, and above all to the vocation of philosophy, it seems fitting that at its close I should briefly recount the incidents of good fortune with which I have been blessed. With the exception of one’s mate, one does not choose one’s family—parents, siblings, offspring, and in-laws. In these respects, I experienced good fortune, but not entirely. My parents came from good stock, as evidenced by their longevity and my own. I am grateful to them not only for the genes they bestowed on me, but also for their wise and benevolent treatment of me as a child, a schoolboy, and a college student.

My mother was a schoolteacher, disposed to encourage study on my part. My father’s German upbringing led him to demand excellence in that performance. Anything less than an A-A-A report card from school was severely frowned upon. In addition,I had the good luck of being their firstborn child, as my sister, Carolyn, will testify about the less-privileged status of being the second child. Though marriage falls within the range of free choice, it is also partly attended by unforeseeable consequences that are in the realm of chance. I was less fortunate in my first marriage than in my second. At my eightieth birthday party, I proposed, with regard t0 marriage, the maxim that if you don’t succeed at first, try again. I did, and it has worked wonderfully well.

I think I summed this up at Caroline’s fiftieth birthday party, when I toasted her as “my best friend and severest critic.” It has been said that the smile on Adam’s face in the Garden of Eden betrays his enjoyment of the fact that he had no mother-in-law. In spite of the fact that Eleanor Pring, Caroline’s mother, was my mother-in-law, I still smile about my association with her and with Caroline’s two sisters, Polly and Margaret. The family I married into by choice has been, by good luck, as good for me as the family of my birth. Having two adopted sons in my first marriage with Helen was clearly a matter of choice. My second marriage with Caroline gave birth to two children, both boys, also matters of choice. But how Mark and Michael, the first two, and Douglas and Philip, the second two, have turned out has not been entirely within my control, or within Helen’s or Caroline’s.

I found the job of being a father taxing and difficult. I am quick to confess that I sometimes shirked my duties, did not devote enough of my time and energy to being a parent, and, in addition, was probably not temperamentally inclined to do better. Much that happened in the course of their upbringing may have been my fault, which I regret and for which I have tried to make amends, differently in each of the four cases. The four boys have matured at different rates of speed and under different circumstances, but the good fortune that I can now report is that they have finally developed into good human beings, enjoyable to be with, as well as good citizens.

Only the first two, Mark and Michael, are now married and have children—my grandchildren—to whom they are good parents. I hope I live long enough to see the other two, Douglas and Philip, married and with anticipated offspring. After one’s family, comes one’s friends. Here, too, I have been extremely fortunate. In a sense, of course, one chooses one’s friends, but acquaintance with the individuals with whom one later elects to develop a friendship is a happenstance.

Only the first two, Mark and Michael, are now married and have children—my grandchildren—to whom they are good parents. I hope I live long enough to see the other two, Douglas and Philip, married and with anticipated offspring. After one’s family, comes one’s friends. Here, too, I have been extremely fortunate. In a sense, of course, one chooses one’s friends, but acquaintance with the individuals with whom one later elects to develop a friendship is a happenstance.

Two individuals whom I became acquainted with accidentally because they happened to be students of mine in my early years of teaching at Columbia University, Clifton Fadiman and Jacques Barzun, have developed into lifelong friends, and have also become the friends of my wife, Caroline. I cannot recount all the ways in which friendship with them has influenced my life and my work; I am grateful that they have grown old along with me and are still alive.

The third friend of my early years, no longer alive, was Robert Hutchins, but as long as he lived, he and I were close friends. But my good fortune in meeting Bob in 1927 when he was acting Dean of the Yale School, was both so accidental and so consequential, that I must repeat here the story about it that I told in Philosopher at Large. (pp. 107-111) In 1925-1926, I wrote my first book, Dialectic, published in 1927. In it, while describing the process of argument and disputation, I dropped a footnote which said that this process is exemplified in the Anglo-American law of evidence. C. K. Ogden was editor of the series in which that book was published, and while visiting Hutchins at the Yale School early in 1927, Ogden was carrying the page proofs of one thirty-two-page unit from my book. It just happened to include the page in which I had placed that footnote about the Anglo-American law of evidence. While talking to Hutchins about other matters, Ogden mentioned me in a complimentary fashion and gave Hutchins the thirty-two-page unit of page proof he had been carrying in his pocket. So far, everything that happened was pure chance.

At that time, Hutchins was not only Acting Dean, but was also Professor of the Law of Evidence. The footnote caught his attention and, in June, he wrote me a letter, mentioning the footnote which he thought signified that I had a lively interest in the law of evidence. He invited me to come up to New Haven sometime that summer to discuss with him problems in the laws of evidence on which he was currently working. Now free choice came into play. Up to that point, I knew just enough about the law of evidence to make that footnote I had written substantially correct, but nothing more. I must have thought at the time that the invitation from Hutchin’s opened up an academic opportunity of which I should take advantage. So I wrote to Hutchins accepting his invitation and setting the time for my visit to New Haven in early August. I then spent the intervening time in July studying the law of evidence, by taking out of the law library J. H. Wigmore’s five-volume classic textbook on the subject. Since the brief opening pages of each chapter contained Wigmore’s explanation of the law on that subject, followed by pages of discussion of cases in the federal and the forty-eight state jurisdictions, I could read through Wigmore’s five volumes, skipping all the pages dealing with cases. As it turned out, when I met with Bob Hutchins in August, I appeared to him to have a firm grasp of the underlying principles of the law of evidence, and we hit it off in general. Shortly after my visit, I received a letter from him inviting me to leave Columbia and join him in New Haven to work with him on some essays he was planning to write about the psychological and philosophical aspects of certain rules of evidence, especially the hearsay rule.

I turned his invitation down, for no other reason, so far as I can remember, other than my unwillingness to change my residence from Manhattan Island, where I had been born and reared, to what, in comparison, was the sleepy little village of New Haven. My refusal to move to New Haven did not divert Hutchins from his aim to get me involved in work on the law of evidence. He came down to New York to persuade Young B. Smith, then Dean of the Columbia Law School, to have me work with Jerome Michael, his Professor of the Procedural Law of Pleading and Evidence. I did so, while still remaining an instructor in psychology. We co-authored a book, entitled The Nature of Judicial Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of the Law of Evidence, published in 1931.

I turned his invitation down, for no other reason, so far as I can remember, other than my unwillingness to change my residence from Manhattan Island, where I had been born and reared, to what, in comparison, was the sleepy little village of New Haven. My refusal to move to New Haven did not divert Hutchins from his aim to get me involved in work on the law of evidence. He came down to New York to persuade Young B. Smith, then Dean of the Columbia Law School, to have me work with Jerome Michael, his Professor of the Procedural Law of Pleading and Evidence. I did so, while still remaining an instructor in psychology. We co-authored a book, entitled The Nature of Judicial Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of the Law of Evidence, published in 1931.

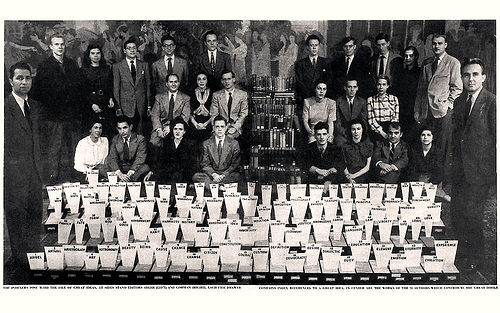

Not only did that result in my friendship with Jerome Michael as long as he lived, and with whom I wrote another book, Crime, Law and Social Science, published in 1933, but it also led to a whole series of fortuitous consequences that represented a train of good fortune at work in the making of my life. First of all, when Hutchins in 1929 became, at the age of thirty, President of the University of Chicago, he invited me to join him there as an associate professor in three areas—in the philosophy and psychology departments and in the law school. My salary as a Columbia instructor, $2,400 a year, was to be increased to $6,000. Quite apart from that advantage, I had the good sense to perceive greater academic opportunities for me at Chicago than I would have had had if I had remained at Columbia. Since I was not yet disillusioned about the “Joys” of academic life, I went to Chicago, not only to teach in the philosophy and psychology departments and in the law school, but primarily to conduct a great books seminar for entering freshman in the college, with Bob Hutchins as my co-moderator. That was an opportunity I could not turn down, and my taking it has had many consequences, all fortunate for me. William Benton had been a classmate of Bob Hutchins at Yale.

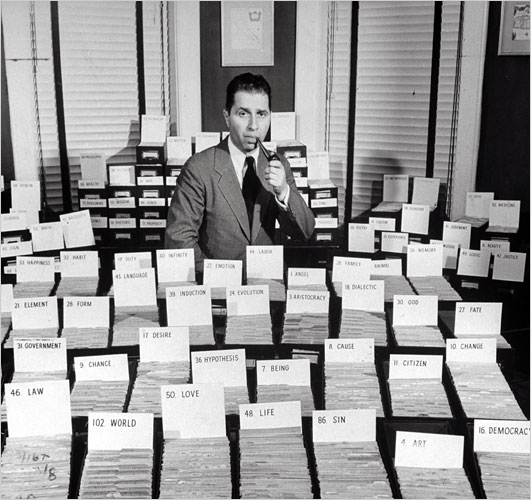

After he retired from the advertising firm of Benton and Bowles, Hutchins brought Benton to the University of Chicago, appointing him Vice-President in charge of Public Relations. Through my close association with Bob, I naturally came in contact with Bill Benton. This developed into a friendship that had many fortunate consequences for me, principally among which, after Benton became CEO of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., was my becoming Bob’s Associate Editor of the first edition of Great Books of the Western World, my producing the Syntopicon that went with that set, my eventually succeeding Bob Hutchins as Chairman of the Britannica’s Board of Editors, and my becoming Editor in Chief of the second edition of Great Books of the Western World. That is not all the good fortune that derived from my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He departed in 1951 from the University of Chicago to become Vice-President of the Ford Foundation. By that time I had become completely fed up with academic life, and, as a result of my creating the Syntopicon, I wished to spend my philosophical energies on producing the Summa Dialectica, a project I had conceived in 1927 when I wrote Dialectic.

After he retired from the advertising firm of Benton and Bowles, Hutchins brought Benton to the University of Chicago, appointing him Vice-President in charge of Public Relations. Through my close association with Bob, I naturally came in contact with Bill Benton. This developed into a friendship that had many fortunate consequences for me, principally among which, after Benton became CEO of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., was my becoming Bob’s Associate Editor of the first edition of Great Books of the Western World, my producing the Syntopicon that went with that set, my eventually succeeding Bob Hutchins as Chairman of the Britannica’s Board of Editors, and my becoming Editor in Chief of the second edition of Great Books of the Western World. That is not all the good fortune that derived from my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He departed in 1951 from the University of Chicago to become Vice-President of the Ford Foundation. By that time I had become completely fed up with academic life, and, as a result of my creating the Syntopicon, I wished to spend my philosophical energies on producing the Summa Dialectica, a project I had conceived in 1927 when I wrote Dialectic.

I could not do that as a Professor of Law, which I had then become at the University of Chicago. In 1952, through Bob’s good auspices, I received a large grant from the Fund for the Advancement of Education, established by the Ford Foundation to establish the Institute for Philosophical Research, of which I have been the President since 1952. The Institute produced the two volumes of The Idea of Freedom, after eight years of research and writing. It later produced dialectical treatments of the ideas of justice, happiness, love, progress, beauty, and religion and, after operating in San Francisco from 1952 to 1963, it was moved to Chicago by Bill Benton when he wanted me there to work editorially for Encyclopaedia Britannica, while at the same time directing the work of the Institute for Philosophical Research.

As I have said earlier in this book, if I had remained at the University of Chicago after Bob Hutchins left it, I could never have done the philosophical work that has been the joy of my last forty years. Bob’s enabling me to leave the University of Chicago and all the distractions and intrigues of academic life, and his enabling me to establish the Institute for Philosophical Research as the ivory tower in which the kind of philosophical work I wished to do could be accomplished, was certainly the greatest stroke of good fortune In my professional life. I am still not finished with Bob Hutchins as my guardian angel. It was through his friendship with Walter and Elizabeth Paepcke that I also became their friends, and it was through them (as I have related earlier) that I became involved in the Aspen Institute after Walter established it in 1950. Meyer Kestnbaum, CEO of Hart Schaffner and Marx, another friend of Hutchins and mine, brought the Institute for Philosophical Research to the attention of Arthur Houghton, Jr., at a conference held at the Corning Glass Works that Arthur attended.

I subsequently met Arthur at a conference in New York, which was sponsored by the Institute for Philosophical Research while it was working on the idea of freedom. That led to Arthur Houghton’s becoming a substantial contributor to the budget of the Institute after the Ford Foundation grant expired; and, more important than that, Caroline and I developed a close friendship with Arthur, with whom we traveled extensively abroad. There is still one further consequence of my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He introduced me to Henry Luce, the co-founder of Time magazine, and to his wife Clare, both of whom, as I have related, came to Aspen in August of 1950. We became friends and Caroline’s and my friendship with Clare continued many years after Henry’s death.

I subsequently met Arthur at a conference in New York, which was sponsored by the Institute for Philosophical Research while it was working on the idea of freedom. That led to Arthur Houghton’s becoming a substantial contributor to the budget of the Institute after the Ford Foundation grant expired; and, more important than that, Caroline and I developed a close friendship with Arthur, with whom we traveled extensively abroad. There is still one further consequence of my friendship with Bob Hutchins. He introduced me to Henry Luce, the co-founder of Time magazine, and to his wife Clare, both of whom, as I have related, came to Aspen in August of 1950. We became friends and Caroline’s and my friendship with Clare continued many years after Henry’s death.

I do not know this for a fact, but I think Clare had something to do with the cover story in Time about me and the Syntopicon, written by Henry Grunwald, who was then Senior Editor under Otto Fuerbringer as Managing Editor. In any case, I have enjoyed my friendship with Henry Grunwald in the subsequent years when he became Managing Editor of Time and then Editor-in-Chief of Time Inc.; and, after retiring from that position, became U.S. Ambassador to Austria. Caroline and I visited him and his wife Louise in Vienna and spent an enjoyable weekend at the Ambassador’s residence there.

Mentioning my involvement in the Aspen Institute as a fortuitous consequence of the great good fortune of my friendship with Bob Hutchins, I must also mention one other fortunate happenstance. Larry Aldrich, a famous dress designer, came to Aspen to participate in one of my seminars there early in the 1970s. Since then, Caroline and I have become close friends with Larry and his wife Wynn. We have traveled with them on many pleasant excursions here and abroad. Larry, having retired from the dress business, established the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, in Ridgefield, Connecticut. His knowledge and expertise in the field of the visual arts has enriched my life; Wynn’s knowledge of cuisines and gourmet skill in cooking, which my wife Caroline shared, sent them abroad together to cooking schools in Paris and Bologna.

I hope I have now made clear how one stroke of great good fortune—in this case, my friendship with Bob Hutchins—led to a train of consequences, all of them fortunate happenings. There are still others that I have not so far mentioned, friendships that have been fortunate for me, but not connected with Bob Hutchins. One was the influence on my life of my friend Arthur Rubin, a friendship that began in the library of the Psychology Department at Columbia when I was still an undergraduate student in the college. This continued until his death. He saw me through the ordeal of my divorce from Helen and later celebrated my marriage to Caroline. He was extremely helpful to me in the rearing of our children. One thing that I should not forget to mention was the inspiration I got from Arthur for the production of the Summa Dialectica at the time I talked to C. K. Ogden about the idea for my first book. That, by the way, was another lucky happenstance. I met Ogden at a tea party given by Gardner Murphy, an associate of mine in the Psychology Department. Ogden mentioned a book he was editing by Boris Bogslavsky, to be entitled The Art of Controversy. It was that title, I think, which prompted me to outline another approach to the clarification and resolution of philosophical conflicts. Whatever I said caught and held Ogden’s attention. He then and there invited me to submit a draft of the book I had outlined. That was in November. I wrote the book over the Christmas recess and during the January examination period, and delivered it to Ogden on the first of February.Another of my lifelong friendships began when I taught a course in the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago. Philip Rosenthal was a student in that class. After that chance encounter, we met again many years later when we were both guests of Mortimer and Janet Fleishhacker on a cruise of the Greek islands. He helped me through many difficulties in my last years in San Francisco, difficulties both personal and professional.

I hope I have now made clear how one stroke of great good fortune—in this case, my friendship with Bob Hutchins—led to a train of consequences, all of them fortunate happenings. There are still others that I have not so far mentioned, friendships that have been fortunate for me, but not connected with Bob Hutchins. One was the influence on my life of my friend Arthur Rubin, a friendship that began in the library of the Psychology Department at Columbia when I was still an undergraduate student in the college. This continued until his death. He saw me through the ordeal of my divorce from Helen and later celebrated my marriage to Caroline. He was extremely helpful to me in the rearing of our children. One thing that I should not forget to mention was the inspiration I got from Arthur for the production of the Summa Dialectica at the time I talked to C. K. Ogden about the idea for my first book. That, by the way, was another lucky happenstance. I met Ogden at a tea party given by Gardner Murphy, an associate of mine in the Psychology Department. Ogden mentioned a book he was editing by Boris Bogslavsky, to be entitled The Art of Controversy. It was that title, I think, which prompted me to outline another approach to the clarification and resolution of philosophical conflicts. Whatever I said caught and held Ogden’s attention. He then and there invited me to submit a draft of the book I had outlined. That was in November. I wrote the book over the Christmas recess and during the January examination period, and delivered it to Ogden on the first of February.Another of my lifelong friendships began when I taught a course in the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago. Philip Rosenthal was a student in that class. After that chance encounter, we met again many years later when we were both guests of Mortimer and Janet Fleishhacker on a cruise of the Greek islands. He helped me through many difficulties in my last years in San Francisco, difficulties both personal and professional.

Since then, Philip has spent many summer weeks with Caroline and me in Aspen where, auditing my seminars, he has renewed our relationship as student and teacher. A third has been the friendship that Caroline and I developed with Andrew and Shawn Block in Chicago, resulting from the fact that their children and ours were pupils in the elementary grades at Francis W. Parker School. Shawn and Caroline were thrown together by their interest in the affairs of the school. Out of that blossomed the warm friendship that has enriched our subsequent years in Chicago. Glancing over the pages of Pbilosopber at Large to jog my memory of blessings that have befallen me, I found one of great importance to my life as a whole, one so important that I should not overlook it here. It is the fact that, with very few exceptions, all the work I have done in my life has consisted of activities that I consider leisuring rather than tolling; in other words, ctivities that one would engage in if one did not need monetary compensation for doing so, as opposed to the kind of drudgery that no one would undertake without being compensated for it. Let me quote the paragraph from Philosopher at Large that eloquently describes this fortunate circumstance.

Since then, Philip has spent many summer weeks with Caroline and me in Aspen where, auditing my seminars, he has renewed our relationship as student and teacher. A third has been the friendship that Caroline and I developed with Andrew and Shawn Block in Chicago, resulting from the fact that their children and ours were pupils in the elementary grades at Francis W. Parker School. Shawn and Caroline were thrown together by their interest in the affairs of the school. Out of that blossomed the warm friendship that has enriched our subsequent years in Chicago. Glancing over the pages of Pbilosopber at Large to jog my memory of blessings that have befallen me, I found one of great importance to my life as a whole, one so important that I should not overlook it here. It is the fact that, with very few exceptions, all the work I have done in my life has consisted of activities that I consider leisuring rather than tolling; in other words, ctivities that one would engage in if one did not need monetary compensation for doing so, as opposed to the kind of drudgery that no one would undertake without being compensated for it. Let me quote the paragraph from Philosopher at Large that eloquently describes this fortunate circumstance.

Looking back on my life since I left home, I count myself unusually fortunate that, during more than fifty years of earning a living, almost all the work I have elected to do has consisted of tasks that I would gladly have taken on even if I had had an independent income. If leisure work, as opposed to drudgery, comprises all those activities in which one would engage for reasons of intrinsic reward and without need of extrinsic compensation, then most of my paid employments have been largely leisure pursuits…. In between the extremes of subsistence work that is drudgery and leisure work for which one is paid, there lies a spectrum of occupations in which both aspects of work are found in varying degrees of admixture. My good fortune has been that I have had the opportunity to choose the occupations of my life so that they would be predominantly filled with leisure

Suppose that that had never happened. Suppose that after being graduated from college, I went to law school or into business. I might never had gone back to reading the great books again, under the illusion that I had mastered them in my first reading of them. After all, had I not graduated with honors? For all intents and purposes, was not my superior literacy confirmed by the high grades I received? In my first two years of reading the same books that I had read as a student with Erskine, but now reading them again in order to collaborate with Mark Van Doren to discuss them with our students, my eyes were opened to the fact that I had not understood them very well, if at all, on my first reading. In the next five or six years, that discovery was repeated again and again, as I learned more each time I reread the same books I had read before.